Understanding Calls and Puts

Understanding calls and puts is crucial for investors exploring the advantages of stock options

Investors can buy and sell options calls and puts, which are the main types of exchange-traded options. Please refer to this article for an overview of options trading for beginners.

Options can expand the toolkit of investors and leverage their capital. For instance, they allow investors to secure the purchase of stocks at a fixed price by paying a premium, and decide on the purchase of the underlying stocks at a later time, depending on how their market prices evolve. Likewise, investors anticipating market downturns can also consider buying option puts, which can help them hedge their portfolios if stock prices decline, or profit from the price drops.

Here is a brief explanation of the four main types of options trades available for traders and investors, with the basics of calls and puts explained in a simplified manner:

- Buying Option Calls. Buying a call (buy to open), by paying a premium, gives option call holders the right, but not the obligation, to exercise the option call and buy the underlying stock at the strike price. Once it has been bought, the call can be resold (sell to close) to other traders in the market to exit this position, without the need to exercise the contract.

- Selling Option Calls. Selling a call (sell to open) enables the call sellers to collect the premium, and creates the obligation to sell the underlying stocks at the strike price, whenever the buyer or the call holder decides to exercise their option. If the seller of the call already owns the underlying stocks, these trades are called covered calls. If the seller does not own the stock, these trades are called naked calls and would require the seller to buy stocks in the marketplace when the calls are exercised by the buyers. Selling naked calls is particularly risky because there is no limit to the potential losses for the seller.

- Buying Option Puts. Buying a put (buy to open) by paying a premium gives put holders the right, but not the obligation, to exercise the option put and sell their stocks at the strike price. Once it has been bought, the option put can be resold (sell to close) to other traders in the market to exit this position, without the need to exercise the contract.

- Selling Option Puts. Selling a put (sell to open) enables put sellers to collect the premium, and creates the obligation for them to buy the underlying stocks from the buyer or the holder of the option put at the strike price, whenever the holder of the put decides to exercise their option to sell, so the put seller needs to have funds reserved for that purchase.

Because the strike price that investors pay to buy option calls and puts are known to them in advance, the limit of what they could lose if the market were to go in the opposite direction from what they originally expected would be limited to the cost of the premium they paid. The differences between stock calls and puts explained in greater detail are presented next.

Option Calls

One of the most basic types of options trades is buying option calls, which function under a similar logic as when buying stocks. Buying option calls works under the assumption that the price of the underlying securities will go up (a long position) during the time the option is held.

If an option contract is bought and exercised (by paying both the premium and then the strike price), the buyer gets the number of stocks specified in the contract. If an option is bought and held, the call holder keeps the right to trade it or exercise it at a later time, up to the expiration date.

If the price of the underlying stock is then higher than the strike price, the call option is “in the money.” If the price of the stock is lower than the strike price, the call option is then “out of the money.” There is no obligation to exercise option calls bought, and holders could let a contract expire if they see no value in trading it, but will then lose the premium they paid.

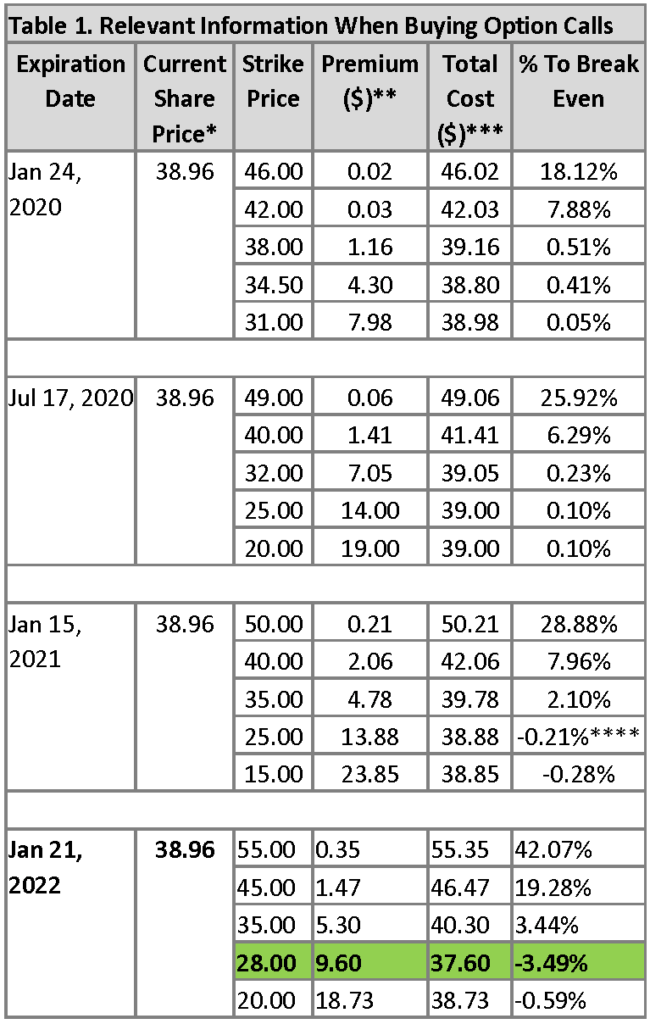

When buying an option call, one key variable to evaluate the price of an option contract is the “percentage to break even,” which enables investors to quickly assess the difference between different options contracts.

The percentage to break even is calculated by adding the strike price plus the premium, and then subtracting that amount from the current stock price. For instance, one option contract may need an 80 percent increase in the underlying stock’s market price to break even, and can be usually be bought for a relatively low premium, while another contract may need to see an increase of only 2 percent in the underlying stock’s market price to break even, but may involve a higher premium cost.

However, if the expiration date of the latter is two years ahead or more, and the stock price were to grow more than 2 percent in that period, the investor would benefit from trading this option, assuming that the underlying stock has not experienced a substantial increase in recent periods, such as the ones associated with temporary peaks following events like quarterly earnings, short-term bubbles, short squeeze rallies, acquisition plans, or other disruptive behaviors that exacerbate its volatility levels.

In practical ways, buying option calls can be understood as an extension of buying stocks, as stock replacements, in the sense that these contracts could translate into the possession of shares in the underlying company.

For instance, investors that want to buy 100 shares of company XYZ but only have enough capital to buy 50 shares can buy an option call, and consider the strike price as their down payment. The investors can then pay the remaining amount at a later time, once they have saved or secured enough money to exercise their option, without worrying about the price of the stock going up, as long as it is at or before the option’s expiration date. Dividends, if any, are issued to the owners of the underlying stock, not to the option holders.

When selling options calls, the percentage to break even is transformed into the chance of profit percentage. To sell calls (covered calls), traders can buy the required number of shares, unless they already own them, and then sell an option for investors to buy those shares at a certain strike price.

If an option is sold and exercised, then the issuer of the call loses the underlying stock but collects both the premium and the strike price. If the option is sold but not exercised, then the issuer of the call keeps both the premium and the underlying stock.

An options strategy explained in Ally Invest’s Options Playbook consists of buying long-term option calls that are deep in the money —those with more than nine months until their expiration date and up to two or three years, to be sold or exercised before they expire— like long-term equity anticipation securities (LEAPS), particularly those with a Delta of 0.8 or greater, which can be used as stock substitutes.

To reduce the level of risk when using LEAPS, investors could choose to limit their trades to option calls with a percentage to break even around 2-3 percent, and even better if such percentage were to be negative, which would mean that the total cost of the option (premium plus strike price) is lower than the market price of the underlying stock.

Option calls with such percentages to break even normally have high premiums and low strike prices, making it more likely that those options will expire in the money, enabling investors to profit if the price of the underlying stocks goes up. With this type of options contract, the risk is kept at a level similar to what an investor would experience when buying the underlying stocks.

If the underlying stock experienced substantial growth in price and the Delta is high, selling the option call may be more profitable than exercising it, since investors can then achieve a greater rate of return in proportion to their invested capital without needing to use the full amount of money that would be required to exercise their option calls.

* Reference date considered: December 26, 2019.

** This cost is per share, so these amounts will need to be multiplied by 100 (for one contract).

*** Total cost is the breakeven point and includes the strike price plus the premium, per share, to get ownership of the underlying shares in the options contract, without considering potential transaction fees.

**** When buying option calls, negative percentages to break even indicate that the strike price of the option contract plus the premium, if exercised right away, would be less than the market price of the stock.

Table 1 provides an example of the basic information involved in buying an option call. In this scenario, the investor has the opportunity to select an option with an expiration date in the future, and examine the different choices available to find one with a low percentage of growth needed to break even. The investor decides to buy one call contract, which contains 100 stocks (if exercised), with an expiration date of January 21, 2022, at a strike price of $28.00, paying a premium of $9.60 for that right. The cost of this transaction would be $960 when buying this option call, plus $2,800 when exercising it, unless the investor decides to sell the option without exercising it.

Option Puts

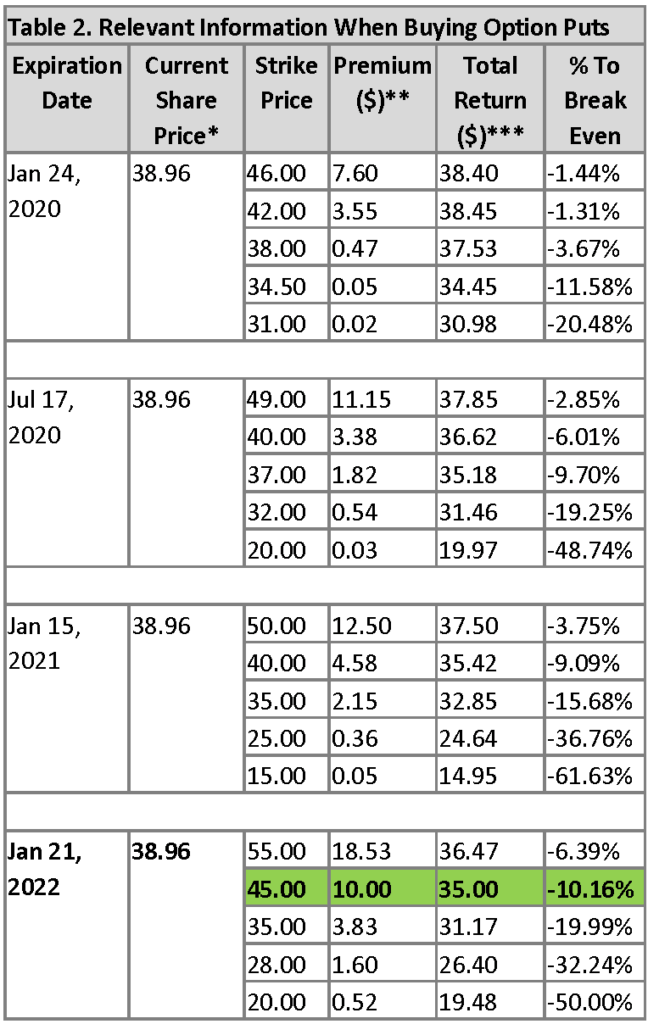

Another type of options trade is buying option puts, which is often favored by investors who work under the assumption that the price of the underlying securities may go down (a short position) during the time in which the put option contract they hold is valid. Table 2 illustrates this situation.

* Reference date considered: December 26, 2019.

** This cost is per share, so these amounts will need to be multiplied by 100 (for one contract).

*** Total return is the breakeven point, which includes the strike price minus the premium, per share, the amount investors would receive for their stock, if they exercise the option (not considering transaction fees).

Option puts work in an inverse way to option calls. Buying option puts can act as insurance in case the price of the underlying stocks or ETFs goes down. Some traders also use them as a shorting speculative strategy when they believe the stock market prices will drop.

Table 2 provides an example of the basic information involved in buying an option put. In this scenario, the investor has come to the conclusion that the price of XYZ may go down and wants to balance the cost and expiration date of the option puts. The investor decides to buy one put contract with an expiration date of January 21, 2022, at a strike price of $45.00, paying a premium of $10.00 for that right.

The costs of this transaction for the put buyer would be $1,000 when buying the put option (buy to open), and would receive $4,500 for the sale of 100 shares of XYZ (for one contract) when that put option is exercised, unless the put is resold or allowed to expire. This trade could prove beneficial to the investor if the stock price were to drop at least 10.16 percent.

When it comes to options, the option calls and put chains data presented by many stockbrokers in their online platforms could in some cases be overwhelming, with many variations to accommodate the different needs of traders.

While some people need sophisticated option schemes, others do not need all that information to trade stock calls and puts. For beginning investors, simplicity in the way of presenting option pricing information is important to avoid confusion. Robinhood, for instance, presents key information like the percentage to break even and the chance of profit percentage in a very clear format, avoiding the need for offline calculations and facilitating the visual screening process.

While this article aimed to have the basics of calls and puts explained, options are a much broader subject that warrants a more detailed study to optimize their potential benefits. Since options pose a significant level of risk, it would also be important for investors to develop a good grasp of stock calls and puts before engaging in actual options trading.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are provided for educational purposes only and are not intended to be investment, tax, or legal advice. Any action taken upon the information on this article is strictly at your own risk. Readers interested in obtaining investment advice should consult a duly licensed investment advisor.