Hunting in the Forest

Hunting and gathering were significant subsistence activities among the Wachiperi of the Peruvian Rainforest

Hunting and gathering were important subsistence activities for indigenous peoples living in tropical rainforests. As Lathrap pointed out, indigenous groups in the Amazon region who inhabited areas distant from the large rivers relied heavily on animal hunting for their subsistence (1973: 84). Clay also explained that the nutrition of indigenous peoples throughout Latin American tropical rain forests largely depended on the calories and proteins from the meat of hunted animals (1988: 11).

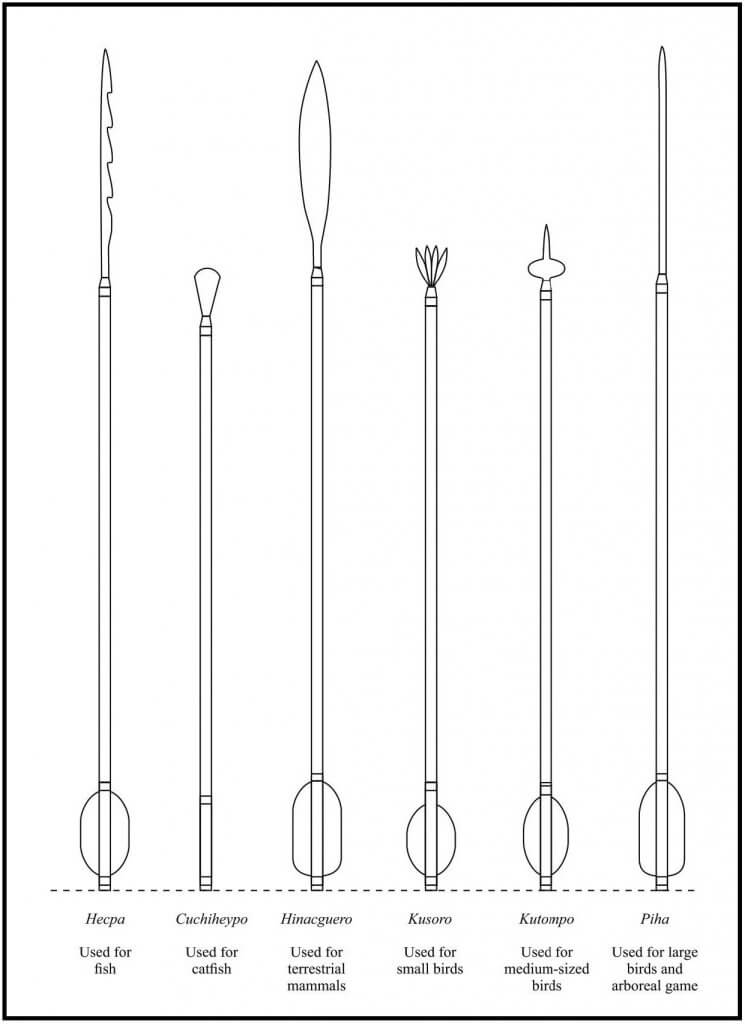

The Wachiperi were not an exception. According to Lyon, “A Wachipaeri did not really consider that he had eaten if there was no meat in the meal, and considerable reluctance was shown to inviting someone to eat if there was no meat available” (1967: 12). Their preferred hunting weapon was the bow and arrow. While the importance of hunting among them has decreased in the last decades, hunting is still significant among them.

Hunting was an activity closely related to the gathering of forest products. These included fruits, roots, leaves, small animals, medicinal plants, and eggs, among others. Some of these were consumed on the spot, while others were carried back to their village, particularly if found in enough quantities.

Today, the main animals hunted by the Wachiperi are small and medium-sized terrestrial mammals and birds. The most common terrestrial animals they hunt are paca, armadillo, peccaries, tapir, deer, brown agouti, and capybara. The most hunted birds are common piping guan, spix’s guan, white-throated tinamou, razor-billed curassow, and macaws.

Before establishing a regular contact with outsiders, around the middle of the twentieth century, the main purpose of hunting among the Wachiperi was for nutritional reasons. However, in the last three decades, the largest hunting expeditions have been organized to celebrate special events. On these occasions, the community gathers and appoints a hunting party whose main task is to go to the forest and bring back abundant meat for the festivities.

Smaller hunting trips are also organized independently by individuals and groups for the celebration of birthdays, the completion a project, and the reception of groups of visitors, among other special occasions. On hunting trips not associated with community events, people often bring their friends along for company, making the hunting trips a more enjoyable experience.

Hunting in Queros is also a form of pest control, a strategy adopted by people to protect their crops, especially cassava and corn. When forest animals come near the agricultural fields in search of edible roots or crops, they often leave visible tracks. When this happens, people in the community set traps or wait for them for the next few days, because it is likely that the animal will return looking for food again. Traps (maspote) are also used by men to capture birds. The animals most frequently found near agricultural fields are paca, collared peccary, brown agouti, and small birds.

Since the presence of animals near these fields is irregular, people who wish to hunt have better chances of finding game in the forest, near saltlicks in particular. Men in Queros use hunting trails that take them through places where animals feed or pass through, according to the season.

Around the middle of the twentieth century, the Wachiperi used to hunt frequently during the day. While using the moon and lanterns as the only sources of illumination worked for night fishing, they were not good enough for hunting. More recently, the greater availability of flashlights has allowed Wachiperi men to go hunting at night as often as during the day.

During the day, hunters usually go on long hikes in the forest, which take them between three and six hours, but most of these hunting trips turn out to be unproductive in terms of meat acquisition. Hunting at night is usually more productive, and requires less travel distance and physical effort.

Though hunting activities among the Wachiperi were normally conducted by men, an exception among the Wachiperi was the case of a woman in the community who hunted armadillos. She went hunting in the company of her dogs, who she said were the ones who taught her how to hunt. During her trips to the forest, she discovered that when armadillos took refuge in their holes it was possible to force them out by introducing irritating plants into their hiding places. She waited by the entrance of their holes and when they emerged she hit them with a machete. On her way back, she usually gathered forest products.

The main reason she started hunting was to have meat to feed her children after her husband died. This woman also taught her daughter how to hunt armadillos, and the daughter in turn transmitted this knowledge to her two daughters. However, none of her descendants carried out this activity on a regular basis. The daughter was busy with subsistence and commercial agriculture, and the granddaughters moved to a nearby town to attend secondary school.

While hunting was a role that women were not expected to perform, if a woman decided to hunt there were no restraints or means of social control in place that prevented them from openly pursuing this activity, like the aggression, myths, of taboos found in other places. The main challenge that prevented women from undertaking this activity was their limited knowledge of hunting.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, women and their children oftentimes joined their husbands on trips to the forest in search of game and gather forest products. The company of women allowed men to travel farther into the forest, and if the hunt was successful women helped carry the meat back.

When a man hunts a large animal and he is alone, he usually comes back to the community to invite others to help him bring the meat to the village. When asked if the meat would stay safe or if other animals would eat it in his absence, a hunter replied that, “It is possible but not likely; jaguars kill their own animals and do not touch the ones we hunt, and we do the same for them.”

In addition to gathering forest products on their own, women also participated in the butchering and distribution of the meat. Once the meat was brought back to the village, the women generally took care of slicing the meat and sharing it with others, based on criteria like their participation in the hunting trip, reciprocity, kinship, friendship, and number of people in the recipient’s household, among others.

References

Lathrap, Donald (1973). The “Hunting” Economies of the Tropical Forest Zone of South America: An Attempt at Historical Perspective. In Peoples and Cultures of Native South America. Daniel Gross, ed. Pp. 83‒95. Garden City, NY: Natural History Press.

Clay, Jason (1988). Indigenous Peoples and Tropical Forests: Models of Land Use and Management from Latin America. Cambridge, MA: Cultural Survival.

Lyon, Patricia (1967). Singing as Social Interaction among the Wachipaeri of Eastern Peru. Ph.D. dissertation. Graduate Division, University of California, Berkeley.

Additional information about the Wachiperi can be found in the book Hunting Practices of the Wachiperi: Demystifying Indigenous Environmental Behavior.