The Fate of Gauchos and Cattle Ranching in Southern Brazil

As landholders and workers adapt to the socioeconomic changes, cattle ranching and agriculture may hold the key to their future

Large-scale ranching in the Americas received both the cultural influence and the livestock from the Iberian peninsula. Escaped herds-turned-wild presented opportunities for free meat and leather.

The sturdiness of the wild cattle, which were descendants of the original animals brought to the New World, allowed some social groups to take advantage of the absence of clear borders and rely on these herds for their survival.

The hunting of wild cattle sustained populations like the nomadic gauchos of the 18th and 19th centuries in the southern South American grasslands.

Cattle was also the main resource for the development of the ranching economy that incorporated new frontiers into the market economy, particularly in areas such as the North American West, the Southern Pampa region, and other areas in Mexico and Venezuela.

These areas developed a subsistence economy based on wild cattle, with intensive use of the horse, which, in the case of Rio Grande do Sul, developed into a regional ranching economy that initially traded in leather and later in jerked meat, articulating the region into an expanding global economy.

The borders between Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina are marked by the presence of the gaucho. The term “gaucho” is associated both with a regional culture and more specifically with ranch laborers.

Despite its more recent promotion to a positive icon of regional identity, in the case of Brazil, and national identities in the case of Uruguay and Argentina, this term was historically pejorative. It was originally used to refer to bandits, outlaws, and deserters.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the unfenced fields and the abundance of wild cattle provided gauchos with meat and leather, the base of their sustenance and material culture.

Present-day gauchos are faced with constraints that force them to adapt to an imperfect reality. Their desire to lead a gaucho lifestyle in the countryside clashes with the modernizing trends in the ranching sector, the urbanization of the landed elite, the increasing role played by commercial agriculture, and changes in their relationships with the landholders they originally relied on.

These changes have intensified a rural exodus. The once thriving countryside in the grasslands is depopulating. The landed elite is changing too, both in response to new economic challenges, and to fulfill their newly acquired needs, desires, and responsibilities.

While ranching families managed to position themselves as intermediaries between the rural population and the centralized and urban state, both landholders and workers are struggling to adapt to the evolving socioeconomic trends in the region.

The combination of ranching and agriculture as a hybrid activity is perhaps the most likely arrangement that will contribute to the permanence of the ranching business. The arrival of agricultural investors meant that ranchers can dedicate themselves to ranching, and at the same time, harvest the profits made possible with the portion of their lands that is rented out for agricultural purposes.

The survival of ranching means that there is a future for the gaucho cowboys, to continue with their lifestyle, even if their numbers continue to decrease and they have to reinvent their way of life to make room for the use of modern techniques in cattle ranching.

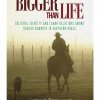

These topics are explained in greater detail in the book “Bigger Than Life: Cultural Identity and Labor Relations Among Gaucho Cowboys in Southern Brazil,” by Luciano Bornholdt.