Types of Book Publishing Companies

Not all book publishers operate in the same way. The size of their operations and the type of arrangements with authors make a significant difference

By Jay Silveratus |Updated April 8, 2020

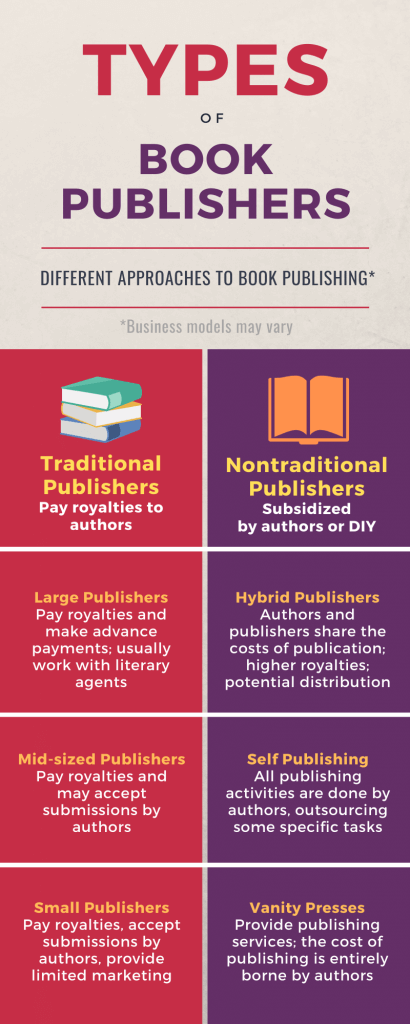

There are two main approaches to book publishing: traditional and nontraditional. Traditional book publishers can be subdivided into large, medium, and small publishers. Nontraditional publishing can be classified as hybrid publishing, self-publishing, and vanity presses.

This article provides additional information about each of these types of book publishers.

Large Publishing Companies

Trade publishers and large book publishing companies are responsible for most of the titles sold in bookstore chains. Examples include the ones known as the “big five,” which include Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster.

These companies are usually the ones that are financially able to provide larger advances to authors after signing their publishing contracts, and offer royalties from the sales of the books they publish, which is a strong motivation to pitch nonfiction works to these publishing companies.

Large companies are also better able to implement more expensive publicity, marketing and advertising campaigns, use teams of salespeople, and benefit from their established relationships in the publishing industry to have their books widely distributed and reach more readers.

These publishing companies, however, are less likely to take a chance on an unknown author, which makes the process more difficult for those trying to pitch their first books.

Authors may have better prospects of publishing a book with these companies by using the services of an experienced and qualified literary agent.

Mid-size Traditional Publishers

Like large traditional publishers, mid-size book publishing companies can be profit-driven or mission-driven, and are usually looking for manuscripts that are likely to attract healthy profits or disseminate the type of knowledge that contributes to their institutional or strategic goals.

Many mid-size publishers are sometimes supported and sponsored by larger institutions, like in the case of university presses, NGOs, media groups, and the publishing branches of professional associations, among others. In the cases of existing affiliations, their publishing goals may be closely aligned with the genres closest to the mission of the sponsoring institutions.

These publishers are usually less likely to offer significant advances on royalties for writers without a proven track record of sales and profits. The earnings for authors may be substantially less, but their publishing processes may be less cumbersome than those of large publishers.

These companies may be more open to niche nonfiction works as well. While the most profit-oriented companies prefer submissions prescreened by literary agents, some of them also accept direct submissions by authors, as long as their submission procedures are closely observed.

Small and Independent Publishers

For writers making their first expedition into publishing, small presses, also known as independent publishing companies, may be a good choice for initial submissions. These publishers are usually more open to experimental and innovative works, alternative points of view, and unusual nonfiction works. Books that do not closely fit within established genres, or those with small and/or specialized audiences, are also more likely to be considered by small publishers. Examples include books of creative nonfiction and fictionalized accounts of real events, also referred to as “faction.”

Some small publishers are also mission-driven, so they are more likely to publish books whose contribution to public knowledge, the dissemination of lessons, or the advancement of a cause is more important than monetary considerations.

The downside of small and independent publishers is that their ability to market the books they publish is often limited, and they usually lack the publicity and dissemination channels enjoyed by larger companies. These constraints oftentimes translate in low volumes of book sales, which is particularly relevant for authors looking to secure economic benefits from their book sales.

Acknowledging this situation, many of these companies encourage the authors to lead the marketing efforts of their books, coaching them in the process of building their author platforms and supporting them in this journey with some limited marketing, advertising, and promotions.

For those authors interested in disseminating their ideas and who do not care much about the economic benefits derived from book sales, small publishers may be an option to consider.

Many small publishers normally accept simultaneous submissions. This means that authors can send proposals to more than one of these publishing houses at one time, which can speed up the acceptance process and can allow writers to make the most efficient use of their time and efforts.

Checking the requirements of each publisher and following their instructions is the best way to ensure that submissions are read and evaluated fairly. Many companies do not accept unsolicited manuscripts, for instance, so it would be wise to review the information on their websites first.

Hybrid Publishers

An article published in Writer’s Digest indicates hybrid publishing “occupies the middle ground between traditional and self-publishing.” These arrangements are also known as assisted publishing, partnership publishing, cooperative publishing, and entrepreneurial publishing, among other terms.

The basic premise in hybrid publishing is that both the publisher and the author provide some of the resources needed to publish their works. In the most common scenario, authors pay for the cost of publishing their books while collecting higher royalties from book sales.

This model reduces the level of financial risk for publishers, since the upfront investment to publish a book is shared with the author. If the book does well in terms of sales, the writer has the potential for a higher level of rewards than the ones offered by some traditional publishers.

Brooke Warner, publisher at She Writes Press and Spark Press, which use hybrid publishing models, explains that some traditional publishers have been asking authors to subsidize the cost of the publication and/or distribution of their books for years, which in practice would place them in the hybrid category, even though they do not publicly discuss those arrangements.

Morgan James Publishing provides a comparative chart of their services in relation to traditional publishing and self-publishing, addressing aspects like bookstore distribution, expected percentage of royalties, number of copies expected to be purchased by authors, etc.

Through their knowledge and contacts in the industry, many hybrid publishers enable the published works of authors to be distributed to bookstores, which is an important consideration to put the book in front of readers if the main format of a book is the print version.

Other hybrid arrangements may be available to nonfiction authors through book publishing companies and other entities, depending on the specific business model of the publisher.

A critical aspect to be taken into account when considering hybrid publishing arrangements is the activities to be conducted by the publisher to distribute and market the book, before and after its publication, and the likelihood that the proposed marketing activities may lead to sustained sales.

While hybrid publishers are willing to take on a greater level of risk by working with new authors than traditional publishers, they are still selective when choosing the books they publish.

For writers with enough cash to subsidize the upfront publication of their works, hybrid publishing houses may provide more added options than the ones available for self-publishers.

Self-Publishing

According to an article published in Fortune, the arrival of Amazon on the ebook scene in 2007 made self-publishing a practical option for many authors who lacked the funding to cover the substantial upfront costs of traditional publication.

Since then, the growth of self-publishing has continued. In 2016, about 40 percent of the four million ebooks on Amazon were self-published, and according to Bowker, the growth rate of self-publishing in 2018 was 40 percent, based on the number of ISBNs issued.

Print-on-demand services — the technology that makes it possible to print small numbers of books, usually after an order is placed — are now readily available and can allow writers to make their books available for readers in print format, including paperback and hardcover editions.

Self-publishing platforms include Amazon’s Kindle, Barnes and Noble Press, Google Play, Lulu, Kobo, Book Baby, and others. While some of these companies will only make the books available on their own platforms, other services like Ingram Spark and Smashwords allow authors to place their books on different platforms such as Apple iBooks, Kindle, BN.com, etc.

For individuals who decide to self-publish, no book proposals, literary agents, or query letters are required. Authors can do all the tasks involved in the publishing and marketing process themselves, or outsource some specific tasks or services to independent providers or those offered by the self-publishing platforms mentioned above, to produce digital and print editions.

While the multiple tasks involved in the process of self-publishing a book may seem intimidating at first, there are plenty of resources that can guide authors in this process. An article published by Ingram Spark offers a brief overview of the main steps involved in the preparation of a book for publication, and there are many additional resources and specialized websites on the topic.

Preparing ebooks can be a faster alternative to publishing a book in print, particularly if a book is about a trendy topic and needs to be disseminated quickly for greater relevance and impact. It also requires less knowledge of formatting and design than producing quality print editions.

Software tools such as Calibre and Sigil can enable authors to convert their manuscripts prepared in a word processor to epub or other ebook formats, and some word processing programs like Scrivener also enable authors to directly export their files as ebooks.

Ebook covers can be created using tools such as Canva, Snappa, or by hiring the services of a designer, which can be done using established services such as 99 Designs. Preparing print editions usually involves knowledge of more complex programs for cover design, interior design, and image processing. However, those services can be outsourced to graphic designers.

Vanity Presses

Authors with enough financial resources can hire the services of vanity presses and have their books published, printed, and placed in the catalogs of book retailers.

Vanity presses provide a platform for the dissemination of messages and ideas in book format that may not have market potential but that are important for authors or their causes. In that sense, this approach may be suitable for manuscripts with a very limited audience, those that are unlikely to lead to substantial sales, those that are not accepted by traditional publishing houses, and those whose authors lack the knowledge or interest in self-publishing their books.

While some vanity presses advertise their services as self-publishing, in practice their services normally take care of the different steps involved in preparing a book for publication and its subsequent listing in the catalogs of retailers, usually under the imprint of the company.

Vanity presses can offer the certainty that the book will be ready within a specific time frame. Authors typically pay an upfront fee for all the book preparation services, in addition to the costs associated with getting printed copies and conducting some basic dissemination activities.

Vanity presses, for the most part, derive their income from the fees charged to the authors for the services they provide, rather than on the prospective income to be generated from book sales.

Authors should be aware, however, that vanity presses are for-profit entities that may do little or no marketing for the book, unless specifically included as part of their services. Even in cases when there are some marketing activities included, the responsibility of leading the design and implementation of the overall marketing strategy, along with the costs associated with the marketing, publicity, and advertising of the book, will remain with the writer.

Another consideration is that some of these companies may hold the intellectual property rights of the titles they publish, which may make it difficult for an author to use a different publisher or self-publish the book later on, due to potentially non-competitive clauses in their agreements.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America warns authors that some of these companies may present themselves as a different type of publisher than a vanity press, often as a marketing ploy, and that since their business model is based on the fees charged to authors, their incentive to invest resources in quality production, marketing, and distribution of their titles is reduced.

Chances are that if a writer sees an ad to get their book published under the imprint of a certain company, and publishing packages start around $2,000 and even go over $20,000 in some cases, the company may be a vanity press. As self-publishing expert Derek Murphy pointed out, in many cases these companies sell services to authors that do not really increase the sales potential of the book.

Other vanity publishers, however, do not openly advertise that there are significant costs involved for authors until the books they submitted have been selected for publication, at a point when the authors have already invested substantial time and effort in the process.

Determining what type of publisher is the most appropriate for a given book, or at a specific stage in an author’s publishing career, makes a substantial difference in the process of publishing a book. The next article in this series provides additional information on that selection process.

This article is part of a series. Click on the link below to read the next article.